These long-held concerns are now critical in a decade where the 79 million U.S. people born between 1946 and 1964 start retiring as soon as this year and larger boomer retirement waves build to peak around 2020-2022.

The concern is that the ebb and flow of U.S. stock markets over the past 50 years is highly correlated with the available pool of household savings channeled into equity investment.

Assuming peoples' prime savings years are those between ages 40 and 65, the proportion of the population in that bracket is therefore key to driving the market. As early as the 1980s, economists feared the impact this may have on U.S. housing markets -- and the recent real estate bust may owe it something -- but stock market connections are more convincing.

The data is alarming. Movements in the ratio of these high savers to both retirees and younger adults has presaged long cycles in real equity prices from the downward funk of 1970s to the subsequent 18-year equity boom through the late 1980s and 1990s as boomers swelled the ranks of prime savers.

The worrying bit for the United States is that ratio peaked in 2010.

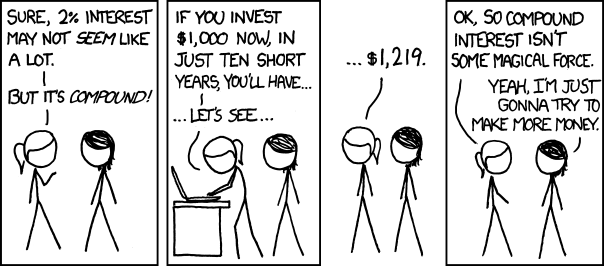

This may very well be the beginning of the long and painful adjustment suggested in Boom, Bust and Echo. On the academic side, I expect these types of weakening returns to slow retirements, especially as Universities shift more and more to defined contribution pension plans., Mark's excellent post on this makes it rather obvious how unimportant returns are to wealth when they are as low as they are now.

The question is how do we break out of this cycle?

Alternatively, what is the best strategy for those of us who have to try and make some sort of plan for the future under these conditions?

And, finally, with bond yields low and the cost of Social Security baked into the financial system, why is this a good time to talk about privatizing the system? Wouldn't we want to do this in an environment with high rates of return on assets to make the new program have a chance to succeed?